The two months at the end of the fourth year of medical school are a heady time for students who have matched with a residency program.

“They’re about to start a new job. Often, they will have to move. And soon they will be getting a paycheck,” said Matthew Soltys, MD, clinical assistant professor of general internal medicine at the University of Iowa Roy. J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine.

But they are also about to take on the responsibilities of a physician, and many first-year residents report that they are not confident in their abilities to perform the Association of American Medical Colleges’ 13 core entrustable professional activities (EPAs) for entering residency.

“The transition from med school to residency is super stressful,” Dr. Soltys said. “You go from, as a med student, having very little power to, as a resident, signing orders that usually get acted upon. So, it’s a big jump in responsibility, and one that literature shows is a source of anxiety for incoming interns.”

That’s why he and his colleagues in the department of internal medicine in 2023 created “Transition to Residency,” which is a two-week, pass/fail elective—placed strategically between Match Day and graduation—that aims to prepare M4s entering an internal medicine residency program to hit the ground running.

“The course gives graduating medical students one last chance to work with the faculty here prior to starting residency,” he said. “And it comes at a time when they are really eager to learn.”

University of Iowa Health Care is a member of the AMA Health System Program, which provides enterprise solutions to equip leadership, physicians and care teams with resources to help drive the future of medicine.

Confidence is key

Transition to Residency covers all 13 core EPAs to refresh students’ knowledge and give them hands-on experience that builds on the education they received in core rotations.

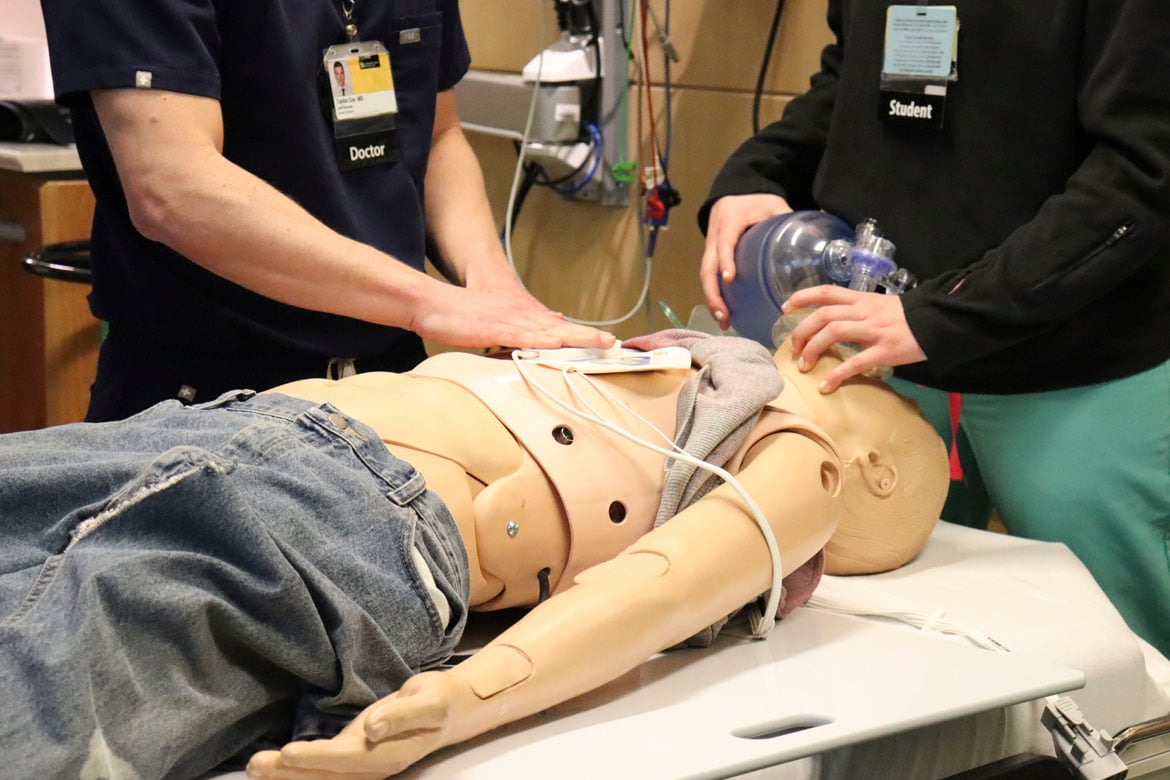

Simulations are an important part, because many students may have only witnessed a situation at some point during medical school, and even that may have been long in the past and only very brief. The simulations focus on tasks that new residents often find most difficult.

A case in point: duties at the end of life. At one station, students work on interpreting end-of-life directives with standardized patient family members who are not aware of the patient’s wishes. At another, they work on pronouncing a patient and then delivering the news that the person has died.

“Medical students don’t take a leading role in pronouncing a patient during their undergraduate medical education, but this could certainly come up in your first month of residency,” said Jennifer Strouse, MD, clinical assistant professor in immunology and one of the program’s lead facilitators.

Another simulation covers using a ventilator. Since most hospital ventilators are usually being used on real patients, the course instead uses a Michigan lung, which simulates human physiology. Facilitators can manipulate it to have different effects, and then students talk through what they're seeing.

Meanwhile, a code-blue simulation gives students experience in a leadership role.

“As a med student, usually when you go to these [code blues], you’re part of a team helping a real patient and you get to observe it,” Dr. Soltys said. “But in the transition to residency, you’re supposed to go from observing to leading, so our students get to go to a simulated case and essentially run it. We also allow them to take timeouts and talk through what their differential is or what they should be asking.”

Before and after students take the course, they take a survey assessing their confidence performing each task using a five-point Likert scale, from extremely unconfident to extremely confident.

“When most of them take the survey before the course, they're putting down all twos and threes, so they’re either somewhat unconfident or neutral,” he noted. “But after the course, everything’s a four or a five.”

The AMA’s Coaching in Graduate Medical Education—A Faculty Handbook offers best practices and recommendations for creating coaching programs in graduate medical education.

Residents help make it happen

One unusual aspect of Carver College of Medicine’s course is that the teaching is performed by residents.

“There's this concept of ‘near peer,’ where someone who is closer to you in education teaches you, because they're not going to teach you as an expert, but as someone who was learning just recently,” Dr. Soltys said.

In addition, residents pick up where faculty have limited resources.

“Courses like this one tend to be very resource intensive. For starters, you need someone who can adequately assess the current learning environment at each institution, because the education that I got at Southern Illinois is different from the education that medical students get here at Iowa,” Dr. Soltys said. “You need someone who can assess that and then develop a curriculum that addresses it, and that requires a lot of faculty time.”

Fortunately, residents have been happy to help, despite their already hectic workloads.

“It hasn’t been an issue,” Dr. Strouse said. “We ask them when during those two weeks will work for them, and then we piece it together like a puzzle. Our program is super supportive of them doing this. So if a resident is on, say, a consult service when we need them, then we just email their supervisor, and that person excuses them for that hour and a half.”

Still, there are those in undergraduate and graduate medical education who chafe at the suggestion that it’s their responsibility to educate transitioning learners—some say it’s the residency programs’ job, while others say it’s up to the medical schools.

“But if no one sees it as their responsibility, then it's no one's responsibility.” Dr. Soltys said.

And then there’s another reason the University of Iowa Department of Internal Medicine is on board with it.

“In a profession where burnout is so prevalent, this course is a breath of fresh air,” Dr. Soltys said. “We’re working with learners who are highly motivated because they’ve just matched and they’re joining our specialty. It’s a great time to interact with them and teach them. It's a highlight of my year.”

The AMA’s Facilitating Effective Transitions Along the Medical Education Continuum handbook looks at the needs of learners across the continuum of medical education—from the beginning of medical school through the final stage of residency. Download the handbook now.