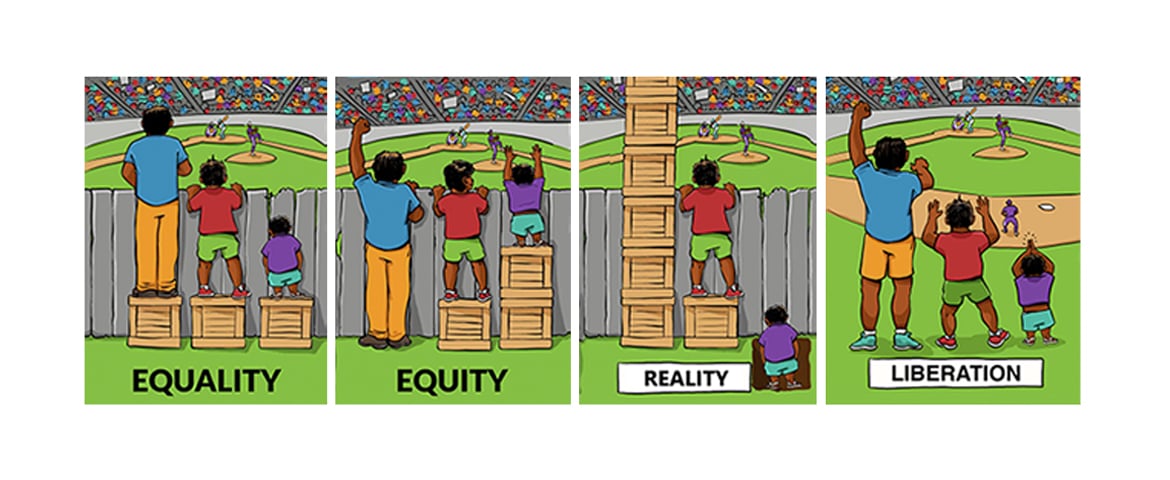

The AMA’s House of Delegates adopted policy that set “health equity”—defined as optimal health for all—as a goal for the U.S. health system, but the concepts of health equity and health equality can be tough to visualize.

Fortunately, artist Angus Maguire did just that for a Boston-based organization, the Interaction Institute for Social Change (IISC) with his widely shared cartoon showing three boys of different heights trying to watch a ballgame from behind a fence with each standing on a box.

The tallest doesn’t need the box to see the game but just having one box to stand on is not enough for the shortest to look over the fence. But, since each kid has a box, that defines “equality.”

In the illustration defining “equity,” the tallest—who doesn’t need a box—doesn’t have one, the medium-sized boy has the one box he needs, and the shortest gets two, finally allowing him to see the game.

“I love that one,” says Mary T. Bassett, MD, director of the Harvard School of Public Health’s Francois-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights. “An equal share does not always advance equity—which is an important point to make.”

The cartoon was mentioned by AMA President Patrice A. Harris, MD, MA, in her “fireside chat” with AMA staff. The IISC reports that there are now hundreds of variations of the highly illustrative illustration—including one used by Aletha Maybank MD, MPH, who has taken on the task of leading the AMA’s new Center for Health Equity.

In presentations, Dr. Maybank shows a third frame labeled “Reality,” which shows the tallest boy standing on seven boxes and the shortest standing in a hole with his shoulders just above the ground. A fourth frame, used by Dr. Maybank and others, is labeled “Liberation.” This one shows the view without a fence and all three figures standing on equal ground.

Image “Reality, Equality, Equity, Liberation,” courtesy Interaction Institute for Social Change (interactioninstitute.org), Artist: Angus Maguire (madewithangus.com), Facebook.

“The reality is that inequities are so great,” Dr. Maybank says. “Our goal is to remove the structural barriers, so we have liberation.”

Dr. Maybank has personal experience with the power a cartoon can have. She said she still gets recognized from a six-year-old video associated with “Doc McStuffins,” a Disney character portraying a young African American girl who is the daughter of a physician and who runs a “clinic” for her stuffed animals and toys.

“This is my claim to fame for me with 4-year-olds—and their parents,” Dr. Maybank said, adding that it’s important for girls to have role models and real-life illustrations that show it is possible for them to become doctors. She’s received letters from girls who say they want to be a doctor just like her.

“As former Surgeon General Dr. Joycelyn Elders said: ‘You can’t be what you don’t see,’” Dr. Maybank says. “Those are the moments when you realize people are paying attention.”

One person who was paying attention to Dr. Maybank was Harvard’s Dr. Bassett, who served as New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene deputy commissioner from 2002 to 2009 before being appointed commissioner in 2014. (She joined Harvard last year.)

In 2009, she lured Dr. Maybank from Long Island’s Suffolk County—where she had launched the Department of Health Services’ Office of Minority Health—to become medical director of the Brooklyn District Public Health Office. Then, in 2014, she appointed Dr. Maybank as the founding director of the city’s Center for Health Equity.

“I was very young,” Dr. Maybank says. “But Dr. Bassett brought me in and she believed in something beyond what was on paper at that time.”

Dr. Bassett says she was impressed by Dr. Maybank’s pediatrics and public health training and how she established the minority health office in Suffolk County while still a resident.

“To be honest, I didn’t feel like I was taking a chance on her,” Dr. Bassett says. “Although she was young, she was already accomplished and she had already displayed initiative and was willing to do whatever it takes to start doing something that’s being done for the first time.

“She already was a national figure and I feel very proud that she has moved from New York City to a national role,” Dr. Bassett adds.

Persistent effort to remove obstacles

In his address to delegates at the 2019 AMA Annual Meeting, AMA Executive Vice President and CEO James L. Madara, MD, described Dr. Maybank as “a prominent national figure in health equity.” He said her first task would be to lead the planning phase of the AMA’s health equity work, which he said will take time, patience and perseverance.

One manifestation of health inequity is that African Americans and patients from other marginalized communities have higher rates of chronic diseases, such as diabetes, asthma and hypertension, and are likelier to report only “fair” or “poor” overall health status.

“What has become clear is that the inequities that persist throughout health care present obstacles to achieving our goals,” Dr. Madara said in his address. “As a nation, and as an association, we need to ensure that when solutions to improve health care are identified, that positive impacts are recognized by all—that one shared characteristic of such solutions is that they also bend toward health equity.”

Dr. Maybank says the experience of launching new health equity operations inside of established organizations has helped her develop a valuable skill set.

“I’ve had these unique opportunities to be an entrepreneur in the health equity and health disparities space within the context of institutions,” she says. This has helped her learn political strategy, the need to “have an inside strategy to do the outside strategy,” and the importance of transparency and being responsive.

“Because I wasn’t an elected official, it gave me more room—or at least, I thought it did—to be transparent about things that didn’t work and were not working to advance equity with community members who usually have some tension with government,” she recalls.

Taking on a position in New York City that had never existed before took entrepreneurship, says Dr. Bassett, who adds that Dr. Maybank arrived with new people and new ideas.

“As part of a younger generation, she is much more media savvy about the uses of other forms of communication than our traditional subway advertisements,” Dr. Bassett recalls. “First in Brooklyn and then citywide, they really did things that—as someone coming from another generation—I wouldn’t have thought to do.”

One example of that forward-thinking approach involved Dr. Maybank’s team taking on childhood obesity and diabetes by highlighting the health hazards created by the empty calories contained in sugar-sweetened drinks. They rented a double-decker bus that played music and was decorated with banners saying “#SodaKills.” The bus stopped in neighborhoods and T-shirts were given to kids with the intent of countering soft-drink company marketing.

“That was something that had never been thought of,” Dr. Bassett says. “That was their charge in the health department—to take an entrepreneurial and innovative route, and she led that charge.”

She adds that Dr. Maybank’s work that may transfer to the AMA could be divided into four categories:

Internal reforms. This included the transformation of three local public health offices into “neighborhood health action” centers, and rebranding an internal education effort as the “Race to Justice.”

“This included ensuring that all employees of the public health department—regardless of their role—be educated about health equity and the impact of racism on health,” Dr. Bassett says, explaining that this included the effects of department hiring, contracts and budgeting.

“Every neighborhood a healthy neighborhood.” This effort identified health disparities among neighborhoods, promoted healthier food and drink choices, and offered physical activities with street dance parties, 5K runs, fitness classes and neighborhood bicycle tours.

Focus on using data and stories. People need to know the numbers but, often, what people respond to are the stories,” Dr. Bassett says. She recalls one data-collection effort that led to a major paper on structural racism being published in The Lancet. Meanwhile, telling the stories behind maternal mortality rates bolstered support for using doulas. “Dr. Maybank was pivotal in promoting a doula program,” Dr. Bassett says. The state Medicaid program launched a doula pilot program this year in Erie County.

Promoting community engagement. “That was a big transformation of the health department,” Dr. Bassett says. “The health department used to say: ‘We’re the experts, we’ll tell you what to do.’ And that doesn’t go over well in communities that have experienced bad treatment disproportionally.”

“If she could do just some of this in her new role at the AMA, that’ll be fabulous,” Dr. Bassett says.

Disconnects in care

Dr. Maybank earned her medical degree at Philadelphia’s Temple University School of Medicine in 2000 and went on to train as a pediatrician—an experience that initially soured her on a health care career. She had studied public health as an undergrad at Johns Hopkins University and earning her master’s in public health from Columbia University in 2006 helped rekindle her spirit and her interest in the healing arts.

What had discouraged her was the disconnect she saw between treating the patient’s illness and attending to those social determinants that may be causing or exacerbating the problem.

“I was very disheartened—and amazed really—at how the medical culture told you that the social worker should take care of social issues related to the person’s life and we shouldn’t be bothered or worry about it as a physician,” Dr. Maybank says. “But so much about pediatrics is about prevention. You can’t prevent problems unless you have a sense of their context in somebody’s life: where they live, where their parents work—if they work—and what do they have access to in terms of supporting wellness and health. All those things are very important.”

She took a class in Native American health that taught her how health and humanity intersect—something that wasn’t recognized in medical culture at the time.

“The experience in public health awakened me, excited me,” Dr. Maybank says. “It was really affirming to me that, yeah, public health is what I wanted to do. It became pretty clear—but I did not anticipate it would be in government, but I’m glad it was.”

Working with the county and city health departments offered practical, hands-on experiences. It also taught her about who has the power to make decisions, who influences those decisions and who doesn’t have any power at all.

She also learned about the power of data, that the scientific community unjustly undervalues the “data of lived experiences,” and the need to look at historical context.

Dr. Maybank recommends that AMA members read The Philadelphia Negro first published in 1899. The extensive survey of Philadelphia’s 7th ward by W.E.B. DuBois, PhD.

DuBois’ work addressed black Philadelphia’s employment, housing, churches, crime and family composition and was ahead of its time in combining ethnography, survey methods, mapping and statistical analysis.

What it also did, Dr. Maybank says, was show how the common perception about the poor conditions that existed in black neighborhoods was wrong.

“We have to first say that there are inequities and explain why they exist,” she says. “Why were the conditions where they lived worse than where white people lived? Before, people thought that blacks were responsible for their own bad condition. But DuBois demonstrated that where folks lived—and the disinvestment and lack of resources—created those differences.”

The nation is on “a pathway to better understand why these differences exist,” Dr. Maybank says, with another key publication being the report, Black and Minority Health, issued by Ronald Reagan’s Health and Human Services Secretary Margaret Heckler in1985.

The report started the examination of why there is such disparity between black and white health and mortality rates. Despite this and much subsequent research on health disparities, the U.S. is one of only three countries where the maternal mortality rate is rising.

Dr. Harris addressed this issue before the U.S. House Ways & Means Committee this past spring, and she highlighted the following factors affecting black, Native American and Alaska Native women:

- Lack of insurance or inadequate coverage prior to, during and after pregnancy.

- Increased closures of maternity units in rural and urban communities.

- Lack of interprofessional teams trained in best practices.

- Structural determinants of health, such as public policies, laws and racism that produce inequities in the social determinants of health, such as education, employment, housing and transportation.

- Stress exacerbated by discrimination that can result in hypertension, heart disease and gestational diabetes during pregnancy.

- Clinicians not listening to black women, resulting in missed warning signs and delayed diagnosis.

Dr. Maybank agrees.

“Women have been saying it for a long time. The data have been saying it for a long time,” she said. “It was very clear that folks have not been paying attention. Maternal mortality is definitely a symbol and a signal that something is not right with the system of health care.”

Search for bright spots

The historical link to many of today’s health inequities dictates that teaching will play a large role in Dr. Maybank’s new position at the AMA as she works to educate staff and others about the context of today’s disparities and why they are so hard to eradicate.

“The question will be how do you teach it so it resonates with folks and creates and spurs action among staff—and among all the folks we work with and our partners as well?” she asks, adding that she believes the strategy will have to be different in each institution and be dependent on the commitment of their leadership.

She said another task of the center will be to look at who in health care is being successful in working toward health equity with success defined as “naming and framing” issues and taking effective action that advances equity.

Right now, she is more familiar with local health departments, and she cites Los Angeles County and Seattle’s King County as departments that are “operationalizing health equity.”

In addition to adjusting to a new job, Dr. Maybank is also becoming accustomed to a new city, as she has moved from New York to Chicago. While she worries about how cold it may get this winter, the warm welcome she has received is encouraging.

“Chicago’s been an activist city and there is a history of organizing here,” Dr. Maybank says. “There’s a health equity community here and people have reached out. Some I already know, many I didn’t. So, personally and professionally, it’s been a great expansion of my own network.”

While Dr. Maybanks is adjusting to the new geography, she has the reassurance of knowing where the AMA stands. The creation of the Center for Health Equity was directed by the AMA House of Delegates as part of sweeping policy on health equity adopted at the 2018 AMA Annual Meeting.

“From my interview and from talking to folks, it was clear that the members and the board wanted to go in this direction,” Dr. Maybank says. “And, talking to Jim [Madara], he’s definitely committed to ensuring that I have what I need to do my job.”

It matters that organizations such as the AMA are putting health equity front and center, Dr. Bassett says.

“The enduring gaps in health by race in the United States are unacceptable, they are unjust, avoidable and can be changed,” she says, adding: “You couldn’t have found a better person to be founding director.”