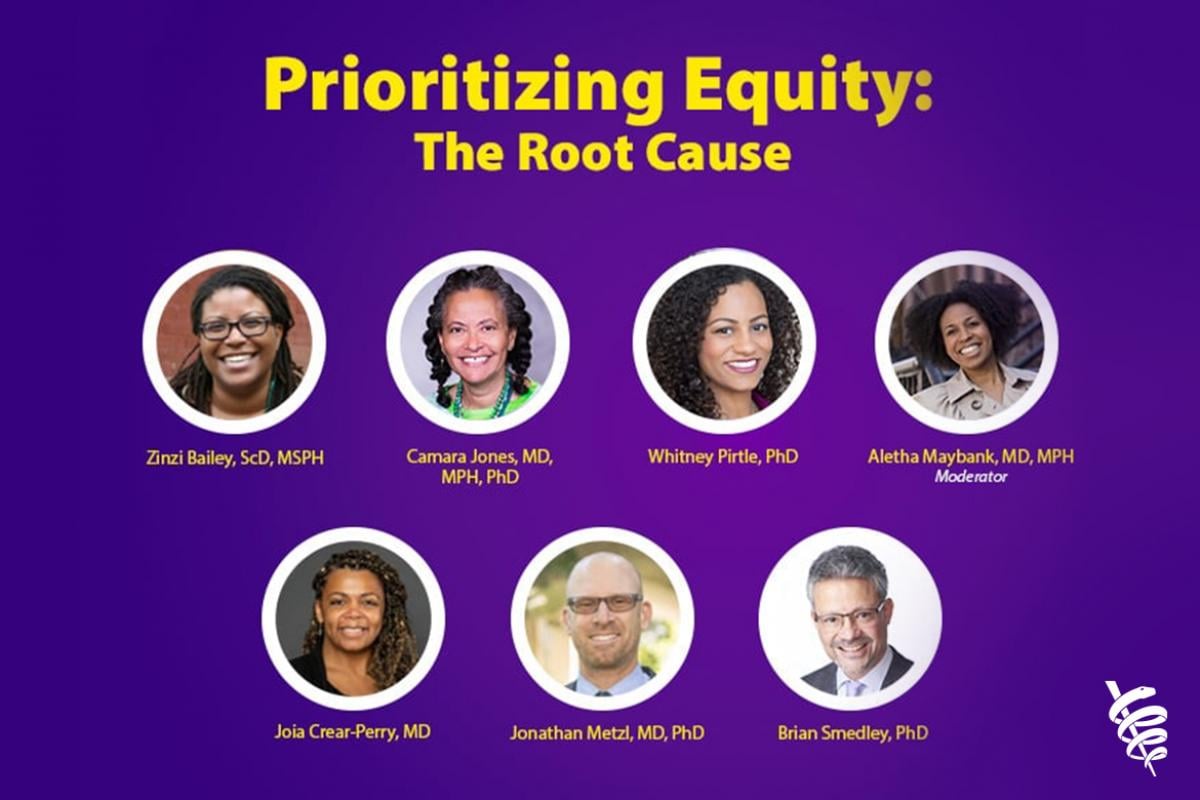

Systemwide bias and institutionalized racism continue to contribute to inequities across the U.S. health care system. The AMA is fighting for greater health equity by identifying and eliminating inequities through advocacy, community leadership and education.

The AMA is committed to creating a culturally aware and diverse physician workforce. Learn more about the AMA's efforts to drive diversity & inclusion with the latest articles and studies.