Dengue

Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral disease. There are 4 types of dengue virus: dengue-1, dengue-2, dengue-3 and dengue-4. Dengue is found globally and infects about 400 million people per year. Outbreaks frequently occur in the Caribbean, Central and South America, Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Dengue is seen in the U.S., in patients who have recently traveled to an area with dengue and due to occasional local transmission, since Aedes mosquitos are common in many areas in the U.S.

The CDC publishes surveillance data on dengue cases in the U.S. The CDC also has a travel advisory page related to dengue, so physicians can alert their patients when outbreaks occur.

Latest health alerts

- March 14, 2025: The CDC issued a Health Alert Network (HAN) on The Ongoing Risk of Dengue Virus Infections and Updated Testing Recommendations in the U.S.

- June 25, 2024: The CDC issued a HAN on Increased Risk of Dengue Virus Infections in the U.S.

Transmission

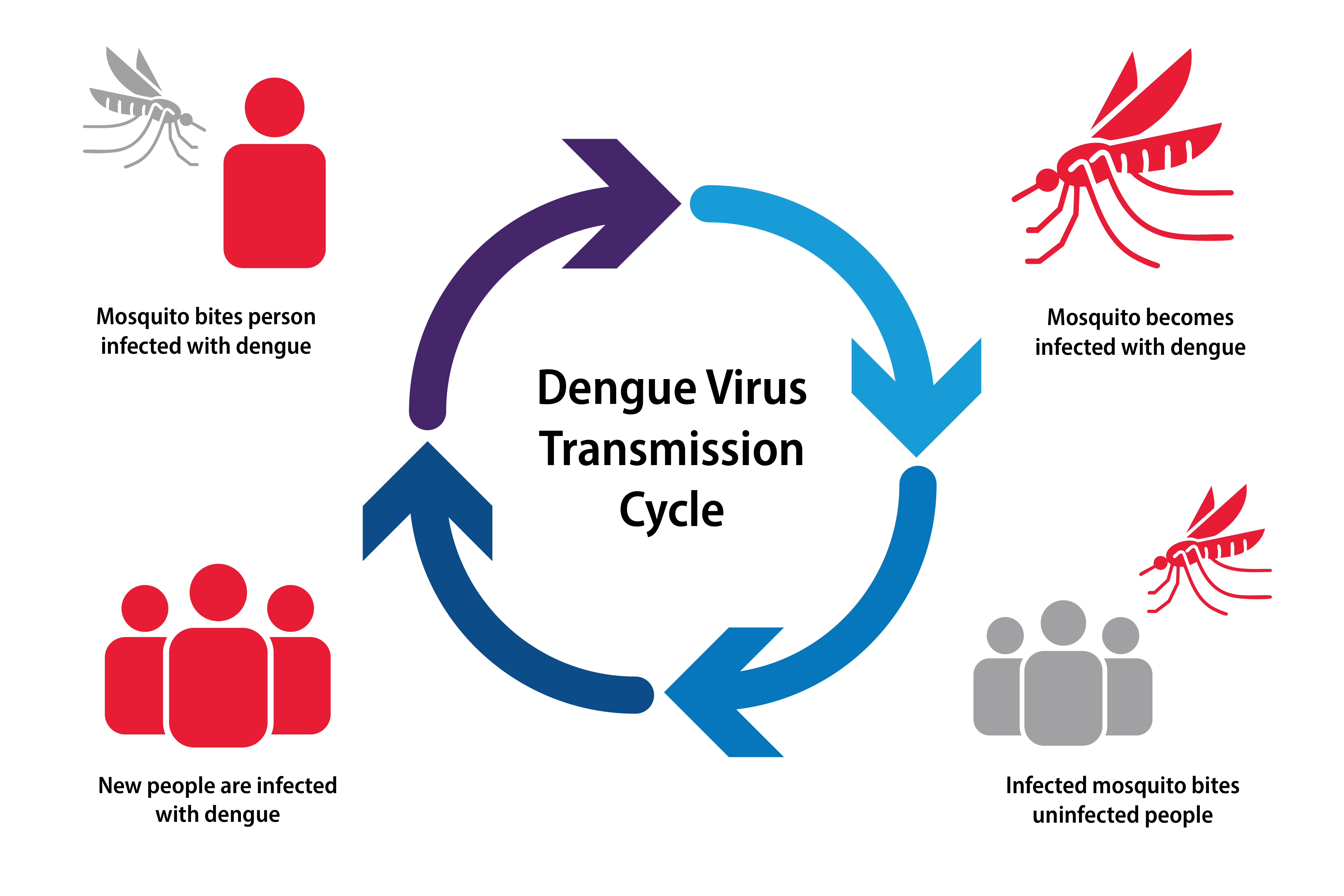

Dengue viral disease is spread to people through the bite of an Aedes mosquito. This same mosquito, which prefers to live at altitudes lower than 6,500 feet, can also spread Zika and chikungunya viruses. Mosquitoes do not get sick with the virus. Rather they bite an infected person, and they carry the virus to other people that they bite. Dengue can spread from pregnant individuals to their fetus during pregnancy. Dengue has also been found in breast milk. Some evidence suggests that dengue can also be spread through sexual contact.

Signs & symptoms

Dengue is an acute febrile illness that causes symptomatic infection in about 1 in 4 people. Symptoms start 5-7 days after exposure and last 2-7 days. Early symptoms are nonspecific–fever, headache, myalgias and arthralgias, maculopapular rash and minor bleeding manifestation like petechia and ecchymosis. About 1 in 20 people with symptomatic dengue will progress to severe, life-threatening infection.

The critical phase lasts 24-48 hours and manifests around the time of defervescence and progresses to symptoms such as vomiting and severe abdominal pain, along with lethargy, hepatomegaly, fluid retention and mucosal bleeding. While most patients will recover from this critical phase, some will progress to severe dengue which is characterized by plasma leakage (e.g., pleural effusions, ascites, hypoproteinemia) and eventual circulatory shock. Hemorrhagic manifestations can also occur, such as hematemesis, hematochezia or menorrhagia.

In patients who enter the recovery phase, plasma leakage slows and extravasated fluid is reabsorbed, stabilizing the hemodynamic status.

People with dengue are not contagious to others. Infection with one of the four dengue virus causes life-long immunity to that particular virus. However, because there are 4 dengue viruses, people can be infected more than once in their lifetime.

Diagnosis

If dengue is suspected, clinicians should ask about their patient’s travel history. Diagnosis of dengue depends on how many days the patient has been symptomatic.

- 0-7 days: Nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) and IgM or NS1 ELISA test and IgM. A positive NAAT or ELISA indicates current or recent dengue infection, but a negative result does not rule it out.

- >7 days: IgM ELISA is the primary test to use; IgM antibodies can be positive for 3 months or longer and are not as helpful for an acute infection. A positive IgM test indicates a presumptive, recent infection.

Tests are available from commercial laboratories and public health laboratories. You can contact your state or local health department to facilitate dengue diagnostic testing. If the patient test negative for dengue, consider testing for Zika, chikungunya and Oropouche, which can have similar clinical signs and symptoms and often circulate in the same areas as dengue.

Prevention strategies

Vaccination

There is one dengue vaccine, Dengvaxia, that is FDA-approved in the U.S., for children and adolescents ages 9 through 16 living in endemic areas (such as Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands and freely associated states such as the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of Marshall Islands and the Republic of Palau). It is approved for children and adolescents ages 9 through 16 with laboratory-confirmed previous dengue infection. It is not approved for people traveling to an endemic area. However, due to lack of demand, Dengvaxia will be discontinued by the manufacturer. Other vaccines are in development.

Treatment

There is no antiviral treatment for dengue. Treatment is supportive care with adequate hydration. Avoid aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid), aspirin-containing drugs and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen and naproxen sodium) because of their anticoagulant properties and dengue’s hemorrhagic potential.

For severe dengue, avoid corticosteroids unless there are concurrent autoimmune-related complications, such as immune thrombocytopenia purpura.

Infection prevention & control

Advise patients who plan to travel to take steps to prevent mosquito bites during travel and for 3 weeks after returning, especially if traveling to an area with frequent or continuous dengue transmission.

Reporting

In the U.S., dengue is a nationally notifiable disease. Immediately notify state, tribal, local or territorial health departments (24-hour Epi On Call contact list) about any suspected case of dengue to ensure rapid testing and investigation. States report dengue cases to CDC.